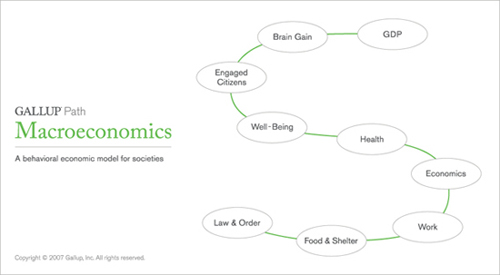

In its first year of existence, Â鶹´«Ã½AV's World Poll made a groundbreaking discovery: What the whole world wants is a good job. This is a significant and actionable insight for business and government leaders -- many of whom not only provide jobs, but more importantly, create the preconditions that allow sustainable jobs to flourish. These preconditions are described by the Â鶹´«Ã½AV Path for Macroeconomics, which shows that job creation requires a stable hierarchy of crucial social elements such as "Law and Order" and "Food and Shelter."

|

But academics, government workers, and businesspeople aren't the only individuals interested in establishing those elements on a global level -- and that's where social entrepreneurs come in. Social entrepreneurship isn't charity, nor is it business. Instead, it applies the principles of both to recognize, create, manage, and sustain solutions to social problems. Muhammad Yunus, who established the Grameen Bank in 1983 and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006, is probably the world's most famous social entrepreneur. His pioneering work in microlending has helped improve the lives of millions of people in the areas of the world that are served by the Grameen Bank, and he has served as a source of inspiration for many other microcredit institutions that have sprung up worldwide.

But, says Lieutenant General Russel Honoré, social entrepreneurship shouldn't be confined to developing countries -- the First World needs it too. General Honoré, who retired from service in 2008, is best known for serving as commander of Joint Task Force -- Katrina. You may remember him as the "John Wayne dude" -- as New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin dubbed him -- who coordinated the U.S. military's relief efforts after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita ravaged the Gulf Coast.

These days, General Honoré travels the country speaking to academics, politicians, and business leaders about the dangers of being unprepared for disasters; he is also a contributor to CNN. His book, Survival: How a Culture of Preparedness Can Save You and Your Family from Disasters, will be published by Simon & Schuster in June 2009.

Why should an Army general care about social entrepreneurship? Because he has not only seen what happens when communities aren't prepared for the worst, but he has also seen what happens when communities don't have jobs available for their citizens. In his opinion, that's just as bad -- and it affects all of us, from Wall Street to Main Street. That's why, he says, all of us should care about social entrepreneurship. In this interview, General Honoré discusses the role of social entrepreneurship in job creation, how the business community benefits from the work social entrepreneurs do, and why Americans should consider social entrepreneurship part of the service they owe their country.

GMJ: You've been a very active voice for disaster preparedness. How are you involved in social entrepreneurship?

Gen. Honoré: I worked with President Clinton on his Global Initiative -- he doesn't call it social entrepreneurship, but that's what it is. I'm on their roster of folks as a resource to talk about preparedness and the impact of disasters on the poor. That's the biggest piece I've played with them. The Clinton Global Initiative is a global network of folks who work for the greater good of the world community. As opposed to just giving people fish, it's showing them how to fish and trying to make more people whole and able to support themselves economically. It's helping someone in Africa get a $100 loan so they can become an entrepreneur and feed their families.

GMJ: How does being prepared for a disaster affect the poor? And what can social entrepreneurs do?

Gen. Honoré: Take Haiti, for example. It's an incredibly poor country. They've cut down 98% of the trees in Haiti because they needed to convert those trees to charcoal [for cooking fires]. So when it rains in Haiti, they get tremendous mudslides. When the mud comes down, it blocks the rivers, and the water builds up and washes out all the crops, which leads to famine. If you don't break the cycle of what people use for fuel, in this instance, they're forever damned. You've got to break the cycle in these impoverished countries, which is what social entrepreneurs do.

I could give examples from right here in the United States. Right now, our healthcare system is basically focused on fixing people. If you go to the emergency room, they'll run tests on you using government-funded medicine. If they figure out you have sugar diabetes, government medicine's going to take care of you. But the problem is, if you come in and you're ninety pounds overweight because you've been eating the wrong foods because you weren't diagnosed ten years ago, maybe now they have to take your leg off. We're in the process of repair as opposed to preventative healthcare, which is expensive and doesn't work as well.

We can do better than that. I think it's going to be primarily in the venue of the social entrepreneurs to push for change -- whether it's change in federal policy or change in the educational system. You see little glimpses of it when the government tells restaurants to stop using certain types of oils to fry food. That's prevention.

GMJ: So there's room for social entrepreneurship even in developed countries like the United States?

Gen. Honoré: Oh, there's need for it here. You know, I was astonished, growing up in a family of twelve kids living on a subsistence farm, when they came out with the Peace Corps. They were sending the Peace Corps to Africa, to Haiti, to South America. And as I looked around, walking back from our outdoor toilet, my idea was: Why in the hell don't we have the Peace Corps here in Louisiana?

We need social entrepreneurs who go into communities and invest themselves in preventative healthcare, and that needs to be integrated into an education system. But at the same time, we need policies that support community programs that teach and that change our culture. If you see these train wrecks coming, you should try to stop them.

I was in Chicago recently, and a lady asked me why, during [the aftermath of Hurricane] Katrina, we were separating black babies from their mamas. And I said, "What in the hell are you talking about?" What really happened was that our helicopters would pick people off rooftops, and often there would be a few adults and several children. Because a helicopter can only carry so many people, we'd take the children first. Of course, those children may have come from three different families, and none of them had parents on that rooftop. But all the adults standing there would say, "Hey, take the kids." So we evacuated them first. But when we took those kids, there was no way to identify them. It sometimes took a couple of months to link them back up with their families. Well, the word on the street was that we were separating kids from their parents. Yet we're a country with the technology to put a computer chip in a dog so we can find it if it gets lost.

GMJ: What room is there for social entrepreneurs in a scenario like that?

Gen. Honoré: I think there's a lot of room for social entrepreneurs to work in communities because they can take on issues with a soft approach. The military approach is: you put steel on a target and you blow it up. That's not the best way to work in some situations, and government policies aren't always the best approach either. If you ask the government for a solution to hunger in Haiti, they'll just send more food. But a social entrepreneur can say, "Let's go in there and see what we can do to raise food and make people more resilient." The government will just give you fish; the social entrepreneur will teach you how to fish. The government will cut your leg off and take care of you for the next fifteen years that you live, while the social entrepreneur will say, "Let's get after diabetes in this community."

GMJ: Do you think that the government can learn something from the social entrepreneurship approach?

Gen. Honoré: I think government in its own way is encouraging social entrepreneurship through programs by providing some funds for programs like Teach For America. But those are national programs. There need to be county- and community-based programs, not just federal flagships, because local programs can do more to help more people.

Government isn't very good at preventing problems, which is why we need social entrepreneurs. Governments try to fix the problem. They try to make sure that nobody goes hungry or that the big banks don't go broke. Local efforts can work toward creating solutions in the community, such as reinforcing kids' education or creating a safe place for kids to go in troubled, drug-infested areas.

GMJ: How does social entrepreneurship benefit business? What good are jobs created by social entrepreneurs to Wall Street?

Gen. Honoré: We don't have a two-tiered society, we have a three-tiered society. It's not just Wall Street and Main Street; it's Railroad Street too. When you export jobs, and we've done that in droves across the United States, you increase the number of people on Railroad Street that don't have a job. Joblessness on Railroad Street drags down Main Street and Wall Street too.

Let me give you an example. I was in Bangladesh maybe twenty years ago, and I saw this lady with a baby on her back and a hammer in her hand crunching bricks. So I asked this embassy official and a Bangladeshi officer I was escorting. I said, "Man, they have machines that could do that. Why do you have that lady crushing bricks with a hammer?" And the Bangladeshi officer turned to me and said, "Let me tell you something, Major" -- I was a stinkin' major at the time -- "Today that lady will earn enough money to feed herself and her baby. We could put a machine there, but then what will she do?" So that's where we need Main Street to create the jobs, to employ the people on Railroad Street. You understand what I'm saying?

GMJ: Maybe -- you're saying that social entrepreneurs can be the link between Main Street and Railroad Street, right? But how do you recommend that people become that link?

Gen. Honoré: We've got to encourage a sense of public service. As you go from being educated to becoming a contributor in the community, you need to understand your power to encourage social entrepreneurship. That's important, because at some point, everyone who a social entrepreneur touches will want to -- for their own personal benefit -- move on to become a capitalist entrepreneur. People who get a start because of a social entrepreneur sustain themselves, and that's also what sustains and creates jobs and grows an economy.

But what becomes the link? A sense of public service cultivates social entrepreneurship, because if you come out of college and you go work in the community and you try to teach people how to fish, you create the conditions for individual capital attainment. And that's your way of giving service to your country. So you're not picking up arms and going to Iraq or Afghanistan, you're working in the community. There are programs that do that, but you don't hear much about them. When these programs become a part of our social awareness, then I think you'll start seeing more people willing to become social entrepreneurs, then become a part of the business community.

But you've got to have a cycle of people getting jobs. I tell you, people in democracy who don't have a job are not free. People thought when we changed the welfare system, then that would solve the nation's ills. It didn't solve the problem because it didn't create jobs. It's as if [people on welfare] have been locked out of a level of entrepreneurship, and it's social entrepreneurs who are finding the ways to let them back in. And that's to their benefit, to the economy's benefit, to the benefit of all of us.

-- Interviewed by Jennifer Robison