Germans' storied work ethic is alive and well. That makes it even more surprising that unemployed workers in Germany actually feel better than working Germans who have bad managers.

Employees can become actively disengaged when their managers neglect them.

First, some background: When Â鶹´«Ã½AV asked employees in Germany what they would do if they inherited so much money they'd never have to work again, seven out of 10 said they would continue working. That number, which surely illustrates Germans' work ethic, has remained stable since 2001.

Though the number of Germans who are out of work has been steadily shrinking, 2.9 million were unemployed in 2012, according to the Bundesagentur für Arbeit. More than half of unemployed workers (54%) report that they find it difficult or very difficult to get by on their current income, according to Â鶹´«Ã½AV research. Almost one-fifth of unemployed workers (18%) say that there have been times in the past 12 months when they didn't have enough money to buy food. It's no wonder, then, that all the unemployed respondents report that they are actively looking for work.

However, even as unemployed workers in Germany lose income, energy, and vitality -- not to mention social connections, emotional support, and hope -- they're actually better off than employed Germans who have bad managers. That's right: In Germany, where 71% would keep working even if they didn't have to, disengagement at work is worse than unemployment.

Only about 30% of actively disengaged employees and unemployed workers are thriving

In 2012, Â鶹´«Ã½AV administered its Q12 employee engagement survey to employed workers in Germany and its well-being assessment to employed and unemployed workers. Â鶹´«Ã½AV asked both groups to , then categorized them as "thriving," "struggling," or "suffering" based on their responses.

Â鶹´«Ã½AV found that 15% of employees were engaged, 61% were not engaged, and 24% were actively disengaged, while 47% of all working Germans were thriving. Among engaged employees, about six in 10 were thriving (62%). Among employees who are actively disengaged, however, only three in 10 were thriving (31%). That result was almost identical among workers who were unemployed: three in 10 were thriving (32%).

Actively disengaged employees are less likely than unemployed workers to say they experienced enjoyment, smiled or laughed a lot, were treated with respect, learned something interesting, or experienced happiness the day before the survey. Engaged employees are more likely to report these positive experiences than other employees and unemployed workers.

- Almost all engaged employees (98%) say they were treated with respect the previous day compared with 85% of actively disengaged employees and 95% of unemployed workers.

- 91% of engaged employees say they experienced enjoyment for much of the previous day compared with 64% of actively disengaged employees and 79% of unemployed workers.

More actively disengaged employees report that they experienced worry, sadness, stress, anger, and physical pain the day before than other employees and unemployed workers. And about four in 10 actively disengaged employees (39%) say they felt stressed for much of the previous day, a finding that has implications for their physical and emotional health.

Even more alarming, 19% of actively disengaged employees say they experienced anger the previous day, compared with 14% of unemployed workers and 7% of engaged employees. Anger in the workplace is a major concern for employers, as it disrupts the workplace and can lead to aggressive behavior that puts coworkers at risk. And actively disengaged employees are the least likely to strongly disagree with the statement "I frequently catch myself being happy when something goes wrong at work," compared with engaged employees (76% vs. 84%, respectively), according to a Â鶹´«Ã½AV workplace poll conducted among workers in Germany in 2008.

Actively disengaged employees also experience more stress at work than employees in other groups. Three times more actively disengaged employees (50%) say they felt burned out due to work stress in the last 30 days than those who are engaged (16%), and this has a negative impact on their lives and health. Actively disengaged employees report missing 7.2 days of work per year due to illness, while engaged employees miss only 4.1 days -- and every day lost to illness costs a German company 275.20 euros on average.

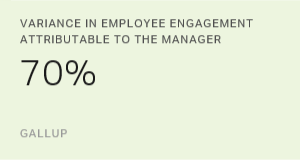

Though unemployment may be difficult and depressing, a terrible workplace might be just as bad or even worse. The problem begins at the local level, often in the relationship between a manager and an employee. Employees can become actively disengaged when their managers neglect them by overlooking their on-the-job needs and expectations.

It's no wonder that 45% of actively disengaged employees would fire their supervisors on the spot if they could, while only 3% of engaged employees would do so, according to a 2010 Â鶹´«Ã½AV workplace poll. The same study shows that significantly fewer engaged employees (4%) than actively disengaged employees (46%) answer yes when asked if they had thought about leaving their current company due to their direct supervisor.

What business leaders can do

It's possible that employees who are actively disengaged are predisposed to lower well-being. But Â鶹´«Ã½AV analyses of engagement in companies suggest that worker engagement levels are significantly influenced by how employees are managed. Workplaces that engage employees increase the likelihood of improving company performance and their employees' well-being and health.

Germany has an entrenched culture of poor people management.

Germany is facing a major economic challenge that will continue to increase in coming years: a shortage of skilled labor. To meet this shortfall, the country's businesses are relying on older employees, who have the lowest levels of engagement. Key drivers of engagement -- such as feedback from supervisors, encouraging development, opportunities to learn and grow, and feeling cared for -- are significantly lower among older workers when compared with younger employees. In spite of older workers' crucial importance to the country's economy, they seem to be disappearing from managers' radar.

The proportion of older workers will grow in coming years as fewer young people join the workforce. Germany's leaders are taking action to lengthen employees' working life. A 2012 law will gradually increase the retirement age from 65 to 67 for all workers who were born in or after 1947, and the retirement age is likely to increase further. For this change to be effective, employees must be physically and mentally able to do their jobs. Workplaces that create environments that disengage employees could potentially harm worker well-being and reduce productivity.

And a lack of skilled labor is hardly Germany's only workforce problem. The country has an entrenched culture of poor people management. Though most leaders are aware of the problem, it has not yet been solved. People management gets very little attention in business management programs. Seniority is rewarded more than talent in too many businesses, and praise amounts to not scolding workers, among other shortcomings.

To overcome these problems, business leaders should make workplace quality a top management priority. To start with, they must:

- Measure and manage employee engagement using metrics such as Â鶹´«Ã½AV's to make sure managers at all levels of the company are meeting their workers' needs and expectations.

- Set engagement goals. Then hold managers accountable for meeting those goals, just as they are expected to meet financial targets. Include rewards for meeting engagement targets in recognition and incentive systems.

- Provide managers with support, training, and coaching to help them understand what employees need from their workplace. If managers are chronic underperformers -- for example, if their team's engagement levels are below average for two or more years -- company executives should determine whether these managers could improve with support, training, and coaching, or whether they should be repositioned or replaced.

- Use a that ensures the right people are chosen for manager roles. Too often, workers are promoted to management roles based on seniority or outstanding personal performance. But the talents required to produce excellence are different from those required to inspire excellence. Managers should be selected based on their ability to engage, care for, and focus on each employee as an individual.

- Call for key changes in manager education at universities, colleges, and vocational training institutions. Most programs focus almost exclusively on educating managers on business economics, administration, and classical management theories. But learning to manage business strategies and processes is not enough. These programs should place an equal emphasis on the skills needed to manage and engage workers, because strategies and processes are only as good as the people who execute them.

About four in 10 companies in Germany (36%) have no employee survey in place, according to a study of German companies with more than 500 employees conducted by the Wiesbaden Business School and 2hm & Associates GmbH. Of the companies that do survey their employees, most ask no questions related to management behavior (77%) and don't use the feedback they get (78%).

People must become a priority

Clearly, managing and engaging employees is not a big priority for companies in Germany. This must change. Companies need to ask the right questions and measure engagement down to the workgroup level. Then executives should focus on taking action at the local and enterprise levels. Managers must be trained and coached on employee engagement and held accountable for engaging their employees. Companies that care about boosting profit and productivity must not let their workplaces become more emotionally, socially, and physically destructive than unemployment.

Well-Being Categories

Â鶹´«Ã½AV classifies respondents' well-being as thriving (strong, consistent, and progressing), struggling (moderate or inconsistent), or suffering (at risk) according to how they rate their current and future lives on a ladder scale, with steps numbered from 0 to 10 based on the Cantril Self-Anchoring Striving Scale. People are considered thriving if they rate their current lives as a 7 or higher and expectations for their lives in five years as an 8 or higher. People who rate their current or future lives as a 4 or lower are classified as suffering. All others are considered struggling.

Survey Methods

Results are based on telephone interviews conducted as part of the Germany Â鶹´«Ã½AV-Healthways Well-Being Index survey July 28, 2012, to December 21, 2012, with a random sample of 2,151 employed adults and 122 unemployed adults. All respondents were living in Germany and were selected using random-digit-dial sampling. For results based on the total sample of employed adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the maximum margin of sampling error is 2.1 percentage points. For results based on the total sample of unemployed adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the maximum margin of sampling error is 8.9 percentage points.

Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones. Samples are weighted by gender, age, education, region, adults in the household, and cellphone status. Demographic weighting targets are based on the most recently published data from the German Statistics Office. All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting and sample design. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

For more details on Â鶹´«Ã½AV's polling methodology, visit .