Story Highlights

- Hiring highly talented candidates is crucial to business performance

- Inherent biases can affect managers' hiring decisions

- Leaders need to understand biases so that managers can hire the right talent

This article is the first in a two-part series.

The decision of whom to hire is often one of the most important ones managers make in their careers.

When done perfectly, hiring is one activity that makes almost every other management activity an organization does either easier or unnecessary. Most productivity in an organization does not come from the mass of people with mediocre performance. It comes from the leading performers who eclipse their peers through exemplary output.

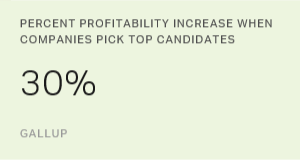

for the job adds to a company's talent profile. In fact, Â鶹´«Ã½AV meta-analysis results suggest that when companies select the top 20% of candidates based on a scientific assessment, they frequently realize: 41% less absenteeism, 70% fewer safety incidents, 59% less turnover, 10% higher customer metrics, 17% higher productivity and 21% higher profitability.

But Â鶹´«Ã½AV's research in behavioral economics shows that managers are not good at predicting who the right people are, because, after all, they are also people. And people, when left to their own devices, are not very good at gauging other people. In other words, managers are not as rational as leaders would like them to be.

Unconscious bias -- something all people have -- crops up in the everyday decisions of life. And, unfortunately, bias can manifest at work leading to a myopic, homogenous workplace.

Understanding Hidden Biases

When people think of hiring biases, they might immediately think of gender and race -- two biases that most companies are aware of and try to mitigate. However, everyday biases can influence decisions and build up over time, becoming a roadblock for hiring top talent. It is important to note that biases are not always barriers for decision-making. In fact, Â鶹´«Ã½AV experts encourage conscious, deliberate decision-making that focuses on attracting and hiring top performers from a diversity of backgrounds.

Biases are filters that shape the way individuals see the world based on prior experience. Our filters are like sunglasses that color the world around us. Being aware of your filters may not stop you from seeing things differently, but it may help bolster your self-awareness and make you more mindful of your seemingly automatic decisions.

Common Biases

When filters go unchecked, they can lead to automatic biases that cause well-intentioned managers to overlook highly talented candidates in favor of mediocre performers, who may match their unconscious stereotypes of what top talent looks like. Managers need to watch for these common biases when hiring:

Framing: When people react to a particular choice in different ways depending on how it is presented, for example, as a loss or a gain. People tend to avoid risk when a positive frame is presented but seek risks when a negative frame is presented.

Hiring managers need to be particularly careful about accepting a subpar applicant simply because a quick hire is needed. When under pressure, a candidate might appear better than they are.

Availability: Relying on immediate examples that come to mind when evaluating a specific topic, concept, method or decision. Hiring managers need to reflect on the entire interview when making the decision to hire and not just on the high or low point of the interview. Thinking about all the experiences with a similar individual over time will yield a more reasoned decision.

Base rate: A pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure that can be neatly expressed in a standard logic system. For example, if a hiring manager had one applicant from a particular previous employer turn out to be really successful, they can't assume that everyone from that company will be successful -- especially if there is better, more objective information on which to act.

Overconfidence: A well-established bias in which a person's subjective confidence in his or her own judgment is reliably greater than the objective accuracy of that judgment, especially when confidence is relatively high. If hiring managers feel too strongly about a person -- whether positive or negative -- they need to question their judgment and remain open that they might be wrong. Managers need to learn as much as possible during the interview, step away from the applicant and evaluate all the available information as objectively as possible.

Anchoring: The tendency to rely too much on one piece of information from a first impression. Anchoring bias happens within the first minutes of an interview -- the manager sets the tone, and the applicant reacts. An applicant might feel rushed during the interview if the manager appears or acts rushed and more relaxed if the manager's demeanor is easygoing.

Escalation of commitment: Making a promise and following through, even if it is a bad decision. If a manager hears that a candidate has been successful somewhere else, yet the candidate responds incorrectly to questions during the interview, the manager might be convinced to hire this person regardless because of the time and energy already invested.

Leaders need to understand the biases of their hiring managers. And to counteract inherent biases, it's crucial to use a systematic, logical approach when hiring. Managers who use a will make better hiring decisions -- and leaders will see better business outcomes.

The second article in this series will discuss how leaders can help managers make better hiring decisions using Â鶹´«Ã½AV's hiring strategies.

Becky McCarville contributed to the writing of this article.