Story Highlights

- Unemployed youth in high-income economies prone to poor physical well-being

- Lack of family support is a complicating factor

- Health problems of unemployed young adults reveal a need for action

We know a lot about the . But new analysis reveals just how bad it can be for .

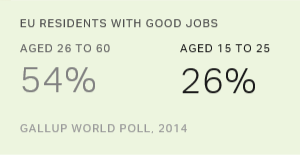

The Â鶹´«Ã½AV-Healthways Global Well-Being Index found that among 47 high-income countries (), the physical well-being of unemployed youth aged 15 to 29 is statistically tied with that of employed adults aged 50 and older -- 26% vs. 24% thriving, respectively.

And in the U.S., where we were able to analyze a sufficient sample size, unemployed youth have worse physical well-being than do employed older adults -- 23% vs. 31% thriving. (Â鶹´«Ã½AV and Healthways define "thriving" physical well-being as consistently having good health and enough energy to get things done each day.)

The same phenomenon is not observed in many lower-income to upper-middle-income economies, where unemployed youth, on average, enjoy higher physical well-being compared with employed older adults. In other words, these findings are unique to unemployed young people in many highly developed economies.

The Stigma of Not Having a Job

What's the cause? A quick answer would be that many of these young adults had poor physical well-being to begin with, preventing them from working. This is possible. But our analysis -- which is based on interviews conducted from 2013 to 2015, with more than 450,000 people aged 15 and older in 155 countries -- also leads to some other viable explanations.

Could the stigma of not having a job as a young person in a highly developed economy be devastating enough that it is similar to adding 30 years of aging to one's physical well-being?

It turns out that unemployed youth with the most education in high-income economies have worse physical well-being than do those with less education. Unemployed youth with college degrees have the lowest physical well-being (14% thriving), followed by those with secondary education (27% thriving) and primary education (28% thriving).

Not only is there something unique about youth unemployment in high-income economies, but there is also something unique about educational attainment levels within them. So what might explain these counterintuitive and troubling findings?

For answers, we turned to , a youth employment program that is active in five countries spanning various income levels: the U.S., Spain, Mexico, India and Kenya. It has supported more than 8,000 youth across these geographies in the past 20 months, and its data and experiences yield two hypotheses that may explain why these outcomes are so prevalent in the U.S. specifically.

First, sharing the burden with a peer group lessens the health effects of unemployment. In Spain, youth unemployment rates reached more than 50% two years ago -- and currently remain upward of 40%. In spite of this massive rate, the physical well-being of unemployed Spanish youth is higher than that of unemployed youth in the U.S., where youth unemployment rates were between 11% and 12% in July 2016.

We hypothesize that U.S. youth who are unemployed could have lower physical well-being because they are an anomaly in a high-employment economy and therefore bear a higher individual cost.

Lack of Family Support Makes Things Harder

Second, unemployment may be harder to bear when family support is absent. Take three reference points: India, Mexico and the U.S. In India, the vast majority of Generation program students are living with several people in their household -- in fact, only 1% live by themselves, and 45% have six or more people in their household.

U.S. youth, on the other hand, are often on their own, with 26% of them living by themselves as the only adults in the household. Mexico is a middle point between the two, with 11% being single dwellers. For reference, Mexico and India, when viewed as part of upper-middle-income and lower-middle-income economies, tend to have slightly higher percentages thriving among young unemployed adults.

Further, Generation has observed that social support services account for a third of U.S. program costs, compared with only a fraction of the costs in lower-income countries, precisely because students rely on friends and family to support them when they are undertaking the Generation program training.

Seeing such a low percentage of young people who are thriving in their physical well-being relative to others reveals a need for action -- specifically for designing specialized programs and support mechanisms for unemployed youth. Much attention has been dedicated to the problem of youth unemployment in developing countries (for good reason), but it is clearly a problem for high-income countries as well. And in high-income countries -- where unemployed youth may suffer from stigmas and lack family support -- it raises important questions about how best to serve them and help them find meaningful work.

A originally appeared in the Harvard Business Review.