Consider the world's official figures on some of the major issues facing humanity. According to the United Nations, roughly 793 million people are undernourished; 767 million live in extreme poverty; and 2 billion do not have a safely managed water drinking service.

The global jobs situation? According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), unemployment is only 5.6%. That's "only" about 260 million people. That feels low considering that for the past decade, Â鶹´«Ã½AV's World Poll surveys have continued to show that the entire world wants a good job.

The problem lies in how the world defines and measures unemployment. The ILO recommends a broad framework of labor force statistics to national statistics offices worldwide. Most countries collect these data using surveys.

These surveys ask people questions like, "Did you work 30 or more hours in the past week?" Then they ask whether they worked for an employer or themselves. If they aren't employed, people are asked whether they are looking for work. The resulting data become the official employment statistics for the country.

You might assume that the world's poorest countries have the highest unemployment rates and the richest countries have the lowest. Not according to the official unemployment figures. Some poorer countries such as Cambodia or Belarus boast some of the lowest unemployment rates in the world.

Rich countries such as France or the greater eurozone have at least three times the rate of unemployment of those poorer countries. In fact, there is no statistical relationship between GDP per capita and unemployment across all countries.

Here is the heart of the problem. Think of subsistence farmers in Africa or people selling trinkets on the street in India. Did they work 30 or more hours in the past week? Absolutely. Though their work is hardly meeting their needs, they still have what global agencies define as work. They are officially self-employed, which means they are not unemployed.

The reason official unemployment figures appear so low in some of these poorer countries is that so many of the truly unemployed are considered self-employed. In the developing world, the self-employed make up roughly 30% of the workforce. This can be confusing because when we hear "self-employed," terms such as "small-business owner" or "entrepreneur" come to mind.

However, most of those categorized as self-employed in the developing world aren't small-business owners or entrepreneurs. When you look at who lives on less than $2 a day, the self-employed appear almost identical to the unemployed. This is because most of these self-employed jobs aren't really jobs.

So, What Is a Good Job?

Let's consider a real job or a good job -- the type of job the whole world wants -- as at least 30 hours per week of consistent work with a paycheck from an employer. Based on this definition, 1.4 billion out of the world's roughly 5 billion adults have a good job.

So who are the other 3.6 billion? About 1 billion people are self-employed; about 300 million work part time and do not want full-time work; about 400 million work part time but want full-time work; 260 million are unemployed; and the rest are out of the workforce. Not all of the self-employed are hopelessly unemployed, but we can conservatively estimate that at least half of them are.

Those 500 million added to the 400 million part-time workers who want full-time work and the unemployed total roughly 1 billion people who are truly unemployed. That figure of about 1 billion, which is just shy of one-third of the entire world's adult workforce of 3.3 billion, would put global unemployment closer to 33% than to the 5.6% that the ILO estimates.

Measuring Whether People Love or Hate Their Jobs

There is another problem with current jobs metrics: There is no figure that measures the quality of people's jobs.

I recently spoke with a global economist about measuring the quality of jobs. She told me her organization was hoping to accomplish this using two metrics: pay and benefits. The problem is that neither metric measures whether people love or hate their job. When people have a job they hate, they are more likely than people who do not work at all to rate their lives poorly.

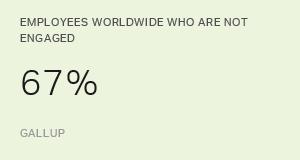

One way to help quantify those intangibles is to ask people about their jobs and their work. Â鶹´«Ã½AV does this through a metric known as employee engagement. Using a short list of questions, we categorize workers into one of three categories: engaged, not engaged or -- worst of all -- actively disengaged.

People who are engaged at work or, in other words, have a "great job," can do what they do best, have the equipment to do their jobs effectively, and have a strong sense of mission and purpose in their work.

Â鶹´«Ã½AV asked our engagement questions worldwide and found that between 2015 and 2016, out of the 1.4 billion adults who have good jobs, roughly 16% are engaged. Out of a global workforce of an estimated 3.3 billion adults who are working or looking for work, then, only 7% or 214 million people have a great job. This means about 3 billion people who want a great job don't have one.

The dream of men and women around the world is to have a good job and, ultimately, a great job. Yet only 214 million people are realizing this dream. Global leaders need to make "great job" creation a top priority. Using better metrics to understand the real jobs situation is a start.

The 2018 Global Great Jobs Briefing is the latest of Â鶹´«Ã½AV's recent reports on the global workplace. The briefing updates the real jobs situation in 128 countries and shows where the greatest gaps remain between the good and great jobs that people want and need.

It complements the report, which provides countries, leaders and organizations with actionable advice on what they need to close these gaps.

Find out how your country rates on good and great jobs in the 2018 Global Great Jobs Briefing.

Learn what countries, leaders and organizations can do to create great jobs in the report.