France is the sixth-largest world economy and has one of the highest productivity rates per hour in the world, ahead of Germany, Japan and the UK. Also the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has just revised growth rate projections for France from 1.8% to 1.9%. Clearly, France is working and working well.

Yet the engagement of its workforce -- defined as employees' enthusiasm for the job and their emotional connection to the workplace -- is very low and falling. Â鶹´«Ã½AV's 2017 State of the Global Workplace report reveals only 6% of workers are engaged, down from 9%, while Western Europe's average is 10%. During the same time, productivity in France increased by one Index Point. The latest data, from February and March 2018, paint a similar picture -- 6% are engaged, 74% are not engaged and 20% are actively disengaged.

So why is employee engagement so low and what are the implications for the economy?

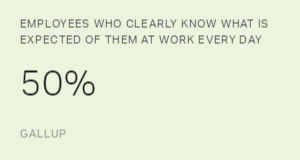

Â鶹´«Ã½AV has been tracking engagement in France and throughout the world for the past 20 years. Despite the apparent simplicity of the questions that gauge engagement (12 questions that measure clarity of expectations, frequency of recognition, quality of feedback and several other aspects of engagement) the explanation for France's low scores are complex. But then, so is France.

Culture and Engagement

France is the land of Jacobin centralization. Deference to the head man, or le chef, has been a cultural norm since Napoleon. To this day, French people place great trust in central authority. The boss is supposed to know best. In the current age of collaborative, coaching-based management, this command-and-control model is slowly fading away but cultural beliefs linger.

However, defiant social reform groups, combined with France's historically strong and vocal unions, have crystallized opposition to corporate leadership. This hostility has instilled a sense of "us against management" or contre les patrons. Thus, no surprise, disengagement can quickly turn into the active, open, highly vocal type.

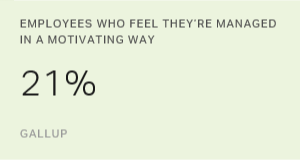

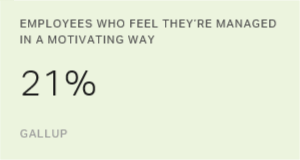

Such disengagement is often a response to serious management shortcomings. Today, 25% of employees in France say their fundamental needs are not being addressed -- that their opinions don't count, they don't have the materials and equipment they need to do their jobs, among other issues -- and less than half say there is someone at work who encourages their development. That can have severe consequences on workers' health and well-being, and in many countries employees just suffer the resulting stress and burnout quietly. In France, frustrated workers stage demonstrations and, occasionally, violent protests.

The perceived inadequacies of management can be traced back, in part, to the French system of educating and training managers. France's elite engineering schools focus on developing highly competent executives with technical skills. Good people management is not a priority. Until the 1990s there were no management courses in these Grandes Ecoles, and people management is a fairly recent innovation in business schools as well.

A degree from a top school is meant to help a graduate climb the hierarchical ladder, not emphasize the graduate's innate management talent, so the probability of a true developer of people achieving a position of power is low.

No wonder, then, that French companies are less judicious in their management selection practices than their foreign counterparts, especially their American ones. That does not imply that France has a shallow pool of management talent. France has innately talented people coaches, but they aren't discerned, hired and trained in big enough numbers to significantly improve French engagement rates.

Therefore, the talent for management remains under-appreciated. It's not unusual for French companies to refuse to move people with a talent for management out of a technical or commercial role. In many other countries, the reverse is true: success in a technical role is mistaken for talent in management and used to justify promotion to management. It also doesn't help mobility that France's labor laws give bad managers life-long positions.

Engagement, Startups and the Impact on the Economy

According to INSEE, the French National Institute for Statistics and Economic studies, startups represent a marginal percentage of employers. Furthermore, many of the perks associated with them, rock walls and game rooms, for example, do little or nothing to improve engagement. Not even for millennials, who, contrary to popular opinion, are much more interested in a workplace that values them and helps them progress than they are lagniappes like rock walls.

And those innovative management practices may not be as good for workers and companies as is sometimes thought, as some insiders report. In an article titled, L'enfer des start-ups, the author of a bestselling book on the subject of startups raised alarm bells and other such accounts are sure to come.

So France's low engagement rate, especially relative to its European peers, can be explained by a set of factors including a cultural mix of deference and suspicion toward management, a lack of good people training for leaders, and a deficiency in addressing fundamental human needs for recognition and feedback. Many other countries have the same issues, yet France's engagement lags behind theirs.

So when will we wake up and acknowledge the modern expectations of work and relationships with managers and peers? And when will France wake up and notice the productivity losses that obsolete models are perpetuating? When will companies take ownership of the misery they cause for one in four workers who are crying out for help?

There's no answer to that, but change will come when business leaders include the cost of disengagement in their budgets. According to Â鶹´«Ã½AV's 2018 findings, active disengagement costs the French economy up to 97 billion euros. But right now, France's high 9.7% unemployment rate makes talent so easy to find that companies may feel nothing justifies the cost and effort of changing their culture -- and some employers think people should feel lucky to have a job at all.

What's more, managers are more likely to be engaged than non-managers in France. Though the percent who are not engaged or actively disengaged are similar among management and employees, 8% of managers are engaged compared with just 4% of non-managers. This gap in engagement may help explain why France's workforce seems to have stagnated on this metric.

Still, even when productivity is high, unemployment is low, and growth rates are sunny, disengagement is a drag on every metric that matters. No matter where a company falls on the business culture spectrum, from vive le chef to contre les patrons, an engaged workforce is a financial boon.

Or France can choose to hide behind the old adage that the French just don't give high scores and that it's about the survey methodology.

Learn more about Â鶹´«Ã½AV's global workforce study and discover how your organization can tap into human capital and revitalize productivity.

- Download Â鶹´«Ã½AV's .

- Watch our on-demand to get vital insights directly from our workplace experts.

- Listen to our podcast featuring Jim Harter, Â鶹´«Ã½AV's chief scientist of workplace management, to hear his thoughts on what workers worldwide need from their bosses.