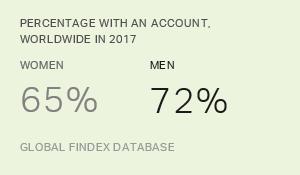

Women with their own bank accounts benefit from having an independent say over how their money gets spent, as well as the ability to receive it, store it, spend it, save it and invest it safely. But as recently as 2011, there was no single source of data that differentiated how women and men access and use financial services.

This data gap was a problem because it meant that the world didn’t have concrete information on the unique challenges women face accessing or using financial services. Policymakers and financial services providers had no metrics to use to benchmark or develop programs and products to meet women’s needs.

Measurements became available when the team at the World Bank partnered with Â鶹´«Ã½AV to develop the first global-scale survey on financial inclusion. Since its first edition in 2011, the Global Findex survey has produced on financial account access, use across a range of products, and financial wellbeing.

Because of the Findex, we know that the gender gap in account access worldwide as of 2021 is six percentage points. We also know that most high-income countries don’t have a gender gap at all, and that many developing economies have narrowed or eliminated theirs with programs and products that appeal to women.

As Women’s History Month draws to a close, we highlight five approaches that are proven to increase financial services access, use and benefits for women, in the hopes that they motivate more economies to pursue them.

1. Government Policies That Tackle Access Constraints

One of the Global Findex survey questions asks unbanked adults why they don’t have an account. Among the most common answers are that financial services are too expensive, that financial institutions are too far away or that the respondent lacks the necessary documentation to open an account.

When we look more closely at the economies that have achieved significant improvements in financial equity over the past decade, we see many benefited from government programs, incentives or fiscal policies that set the conditions for inclusive finance.

One example is India. The country eliminated its gender gap in account ownership from about 17 percentage points in 2011 to effectively zero in 2021. Over that period, more than doubled the total share of adults with an account from about 35% to 78% of the population.

The government did this primarily by coordinating programs to provide digital government-issued IDs and to open bank accounts for the country’s unbanked adults. It was able to grow the total account ownership rate in a way that included women in the expansion.

Yet, women in India today are 17 percentage points less likely than men to use their account to make or receive a digital payment. The end goal of account ownership is for women to use financial services to achieve , including reduced inequality, better jobs and gender equality. Reaching these goals will require narrowing the gaps in how women use their accounts to save, borrow and make payments.

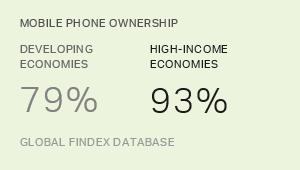

2. Expanded Access to Mobile Phones

Mobile money accounts are basic financial deposit accounts that allow users to store, send and receive money using exclusively their mobile phone. Research in Kenya found that mobile money offers women more financial independence, which highlights the importance of women’s access to technology.

In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, mobile money providers play a significant role in driving financial inclusion for women. Today, about half of all women in sub-Saharan Africa have a bank account -- up from just 20% a decade ago -- including 30% of women who use a mobile money account.

Outside of sub-Saharan Africa, mobile money accounts are also offering women more control over their money. For example, the mobile money account ownership rate in Bangladesh increased to 20% in 2021 from 10% in 2017 and just 2% in 2014.

3. Payment Digitalization That Motivates Account Opening

Global Findex data show that across all developing economies, one in three adults opened their first account to receive a direct payment from the government or from a private sector employer. Digitalizing government payments, along with a strong consumer protection framework, offers a range of benefits for the government and recipients.

Though women are less likely than men to work in the private sector, a higher share of women than men who are private sector employees receive their payments into an account, which makes it easier and safer for women to save money and helps them have more say over how the money is spent.

There’s an to do more. The Global Findex 2021 data estimate that roughly 45 million women with private sector jobs still receive their wages in cash. Digitalizing a share of these payments could give more women formal access to the financial sector and an array of financial services such as auto-deposit savings products.

4. Global Disruptions That Catalyze Behavior Change

It was clear within the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic that the resulting mobility restrictions were driving increases in of all kinds. Lockdowns forced people to use the internet and mobile devices to work, purchase items they would have previously bought in person, and conduct financial transactions.

In 2021, 40% of adults in developing economies who made a retail purchase using a digital payment method -- such as with a debit card, mobile money account or e-wallet, or by using the internet -- did so for the first time after the start of the pandemic.

In some countries, social norms related to household spending led to greater digital payment adoption for women. For example, in Mongolia, 26% of women made their first merchant payment during the pandemic (eight points higher than men), and in Thailand, 33% of women made their first digital merchant payment (six points higher than men).

5. Savings

Savings allow people to invest in the future and deal with financial challenges that arise. Savings are particularly important for women, given the Global Findex 2021 data showing that women are less financially resilient on average than men. “Financial resilience” is the ability to access money to deal with a financial emergency such as an accident or an illness.

In developing economies, only 50% of women say they could come up with emergency money, compared with 59% of men. Even in , women are less likely than men to be resilient.

One reason why is that women are more likely to rely on family and friends for financial support in an emergency, and these social sources can be unreliable. In contrast, people who have and use savings are more likely than people who rely on any other source -- including borrowing or extra work -- to access money without difficulty for an emergency.

Opportunities Remain to Improve Women’s Access

These five strategies represent important areas of progress for women’s access to financial services. There’s still more work to be done. More than half of the world’s 1.4 billion unbanked adults are women. Using these approaches in the right economies through the right policies can help equip more of them with the financial services they need to manage, store, save and invest their money.