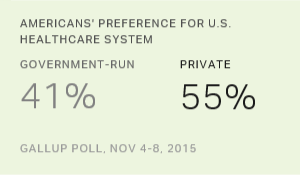

The majority of Americans do not feel that the federal government should take on the role of making sure that all Americans have healthcare coverage. This has been the case for five of the last six years, as I reviewed and as depicted in this graph below.

The question arises as to why this is the case. Americans previous to 2008 did think that making sure all Americans had healthcare was an appropriate role of the federal government. Several things have happened since that point. The recession hit, Barack Obama was elected president, and the Affordable Care Act was fiercely debated and then passed. Additionally, and importantly, the issue of government as the nation's is now second only to economic concerns.

This gives rise to consideration of two fundamental concerns that are almost certainly behind Americans' answers to this question about the role of government in creating universal healthcare.

First, Americans have broad philosophic concerns about the appropriate role of government, which transcend or provide context for any specific instance of the use of government to attempt to address or remedy a social problem. Second, regardless of their philosophic position, Americans have concerns about the practical ability of the government to be able execute efficiently both current and new missions it takes on, a seemingly fundamental concern when the government contemplates taking on responsibility for additional social issues and problems in a massive way.

Neither of these concerns are focused on what I would call the nuts and bolts of what actually would be involved in ensuring that all Americans have healthcare. Proponents of the Affordable Care Act, as we know by this point, frequently point out that Americans, in theory, support some of the individual components of the ACA. This includes such things as guaranteed health coverage regardless of pre-existing conditions and allowing children to stay on their parents' plans until they reach age 26. But that's not the point. The point is that Americans' broadly negative reactions to the Affordable Care Act most likely involve their consideration of the appropriateness and ability of the federal government to take on a very large role relating to a very large component of most Americans' lives.

This reminds me of the famous P/PC distinction made by author Stephen Covey in his The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. The "P" stands for Production and the "PC" stands for Production Capability. As Covey points out, stepping back and addressing the big picture issues involved with Production Capability often means that the specifics of Production will follow along in much better shape later in the process. As Covey says, the P/PC balance "...balances the short term with long term."

In this situation, I call attention to this balance because I think that the PC, or Production Capability, that confronts the country is the government itself, split into the two aspects I mentioned above: the focus on -- big picture -- what the role of the federal government is or should be in addressing major issues, and the focus on -- big picture -- the ability of the government to operate effectively and efficiently.

When the Affordable Care Act was conceived, fought over and then ultimately passed by Congress, much of the emphasis was on lower-level production -- how various components of the ACA would be implemented. These focus points carried with them the implicit assumptions that a) it was the role of the government to be involved in ensuring that all Americans have healthcare, and b) that the government was perfectly capable of directing and helping carry out this mission efficiently and effectively. Proponents of the ACA could have profitably spent more time on these implicit assumptions before they proceeded with the specifics of the law. Addressing the core intent of the ACA directly, the debate could first have focused on this question: "What is and is not the role of the government in modern society, and is it appropriate for the government to take on the responsibility of addressing a major social institution such as healthcare?" The second broad question could have been: "What is the organizational capability of the government to effectively and efficiently take on the role of ensuring that all Americans have healthcare?"

These are the broad Production Capability questions that lie beneath the debate on healthcare, and if they had been addressed more thoroughly first, the public's current view of the ACA might be significantly more positive.

The data clearly indicate, as I noted previously, that the majority of Americans at this point do not accept the general principle that the federal government should be responsible for making sure that all Americans have healthcare, which is the central goal of the ACA. More generally, a majority of Americans that the federal government is doing too much that should be left to individuals and businesses. Similarly, although Americans have positive views of the ways in which certain components of the government do their jobs -- including the military and the U.S. Postal Service -- the overall image of the federal government is the of some 25 business and industry sectors tested. Not a lot of confidence there in the government's ability to tackle massive problems.

So, these Production Capability considerations are the fundamental bedrock upon which any effort to create new, big roles for the government must be built. The Affordable Care Act is, at the moment, very much in terms of its image in the eyes of the public. If President Obama and other proponents of the ACA want to figure out why, they should ponder these more fundamental points. These individuals can profitably look to the analogs of Production Capability -- the fundamental concerns about the role of government and how effectively the government operates -- before dismissing negative reactions to the ACA as just political fallout.

Other than the focus on improving the economy, keeping the government running without shutting down, and protecting the nation from foreign threats, my reading of the data suggests that the American public at this juncture would want their leaders to turn to these big picture questions about government, leaving specific legislative issues until later.