Sixty-five years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in U.S. schools was unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. Cheryl Brown Henderson -- daughter of the plaintiff in the case and president of Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research -- joins the podcast to look back on the landmark decision and what education and life were like for Black Americans before and after Brown v. Board. How has the decision impacted schools today, and where is there still more work to be done?

Below is a full transcript of the conversation, including time stamps. Full audio is posted above.

Mohamed Younis 00:07

Hello, Â鶹´«Ã½AV Podcast listeners. In this episode, as we continue to commemorate Black History Month, we take a look back at another of my favorite interviews. Students of the civil rights movement will recall the moniker Brown v. Board of Education as the name of the historic lawsuit that began the process of desegregating public school systems across U.S. states. Today, we'll listen in to a previous interview with one of the actual litigants of that case, in a discussion that brings home the chilling reality of how recent legally enforced race-based segregation was a reality in the United States. While Brown v. Board, to some, represents the immense progress that's been made over generations, today, most Americans tell Â鶹´«Ã½AV they're actually dissatisfied with the state of race relations in their country. This week, we share the human story behind the famous case, Brown V. Board.

Mohamed Younis 01:12

From our studios in Washington, D.C., I'm Mohamed Younis, and this is The Â鶹´«Ã½AV Podcast. In this episode, we contemplate the 65th anniversary of the monumental Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education with one of the actual plaintiffs from the case. We'll also examine current attitudes across America on the issue of racial segregation in schools today and Americans' views on the best solutions to remedy the social phenomenon. So let's start with the present as we explore attitudes on racial segregation in schools today in America in this week's Data Dive.

Mohamed Younis 1:48

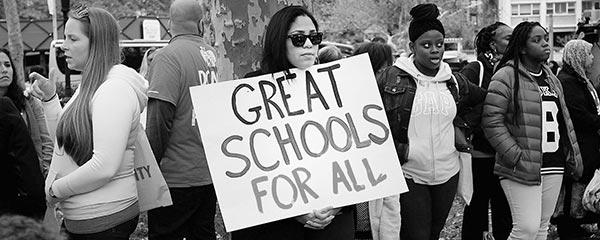

Before we explore the data, it's important to clarify that while racial segregation was mandated by law in the Jim Crow era, today, the problem is more one of racial concentration as an outcome of systemic economic and geographic realities, as opposed to the Jim Crow era's legally mandated racial separateness. Today, 57% of Americans describe racial concentration or segregation in American public schools as either a very serious or serious problem in America. 52% of Whites, 68% of Blacks and 65% of Hispanics share that view. In terms of what to do about it, 53% of Americans say the federal government should take additional steps to reduce racial concentration or segregation in schools, while 45% say it should not. This is one of the questions that most highlighted racial differences in our poll, with 55% of Whites saying the federal government should not take additional steps to address the issue, while 78% of Blacks and 76% of Hispanics say the federal government, in fact, should take additional steps.

Mohamed Younis 2:51

When asked about various policies to address the issue, 79% of Americans favor creating more regional magnet schools that offer specialized courses and curricula; 66% favorite policies that incorporate more low-income housing into suburbs and high-income areas. Six in 10 Americans support redrawing school districts. However, the least support was expressed for requiring school districts to "bus a certain percentage of students to a neighboring school district to make schools more racially diverse." In fact, 55% of Americans oppose busing, while 43% favor it. This was another area where we saw divergence across racial groups. While only 33% of White respondents favor busing, 65% of Black and Hispanic respondents supported the policy. So while most Americans view racial segregation or concentration in schools as a serious issue, there's a stronger overall support for improving the quality of schools and the education they offer, as opposed to busing students to particular schools to tackle the issue. And that's your Data Dive.

Mohamed Younis 04:01

Next. I'm pleased to welcome onto the program Cheryl Brown Henderson, one of the three daughters of the late Rev. Oliver L. Brown. In the fall of 1950, along with 12 other parents and led by a legal team from the NAACP headed by Thurgood Marshall, Rev. Brown and others filed suit on behalf of their children against the local school board. Today, Cheryl's the founding president of the Brown Foundation for Educational Equality, Excellence and Research, an organization that has taken on the task of educating the public and students on this key decision in American jurisprudence. But that work continues today in improving educational opportunities for children, and I know the foundation is involved in some of that work as well. Cheryl, welcome to the program.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 04:42

Thank you.

Mohamed Younis 04:43

I want to start at the beginning. Tell us about your parents, your family and how you all got involved in one of the most iconic cases in American history.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 04:51

It's an interesting story, at least to me. My parents were very young: My dad was in his 30s and mom in her late 20s, and they were really not, they didn't set out to make history or even be social activists. But Kansas has a unique story in and of itself, and I think their involvement is really a continuum of that Kansas story. Brown v Board in Topeka, it turns out, was part of a litany of cases. There had been 11 school desegregation cases in Kansas before Brown -- even three in Topeka. So the NAACP --

Mohamed Younis 05:25

In Kansas alone.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 05:26

In Kansas, yes, alone. And Kansas is unique in that regard, and very proud of that, I have to say, as a native Kansan. And I love educating people about how significant the state of Kansas is to civil rights. Because when people think about flyover country, they really don't think about diversity; they don't think about civil rights. Yet Kansas laid the groundwork with John Brown and Bleeding Kansas, and he successfully halted the westward expansion of slavery during the Civil War. And as a result, Kansas was never a slave state and was proud of that legacy. And after the Civil War, worked diligently to recruit formerly enslaved people to come and help populate the state of Kansas. So it made sense that, not only were they looking at being able to own land and have certain freedoms -- employment. For example, my father was a welder for the Santa Fe railroad. He belonged to a union in that period of time. And you certainly wouldn't think that was possible, because unions have their history of racial segregation. But that was not true in Kansas.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 6:32

So their life experience, although it was kind of a crucible of contradictions, because, yes, we lived in an integrated neighborhood. Yes, he worked in an integrated workforce. However, you could still, you could not try on clothing in department stores. You could not be served at the counter at the Five and Dime. So there were still certain things that Kansas, I guess, acquiesced to the national norm of segregation and how people interacted. Interestingly enough, though, when my father became a pastor in 19-3, he was assigned to St. Mark A.M.E. Church. The assistant pastor was White. And so his family of six children and his wife, they were all members of our church, and he was the assistant pastor. And for an African Methodist Episcopal Church in the '50s, that, again, was something unique for our city, for our state and certainly for our family.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 7:30

So it we, we learned a lot. And I think living in an integrated neighborhood in the midst of all this, a lot of people presume that our experience was like the experience of the South -- like the Virginia case or the South Carolina case; and it was apples and oranges in many ways. And I'll talk about that in a minute as to why I think the Supreme Court then chose Kansas to be the lead case of the cases. So anyway, back to my parents. So my father was looking for a way not to live a marginalized life. African American men were very marginalized, and we talk about that still -- but very true then. He had worked at a mortuary; he worked for a coal company, driving a truck. He boxed in the Golden Gloves because Joe Louis was his idol. And from there he started studying theology and became a pastor and a trained welder for the Santa Fe.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 08:27

So I think part of this willingness, when the NAACP approached him, part of his willingness, I believe, came from the fact that he wanted to make a difference. He did not want to live in the margins of society. Mom was a very typical 1950s homemaker and mom. So she was really not the person out front. But he had that, that interest and that internal fire if you will that, that someone you know, just needed to strike the match and the NAACP, in approaching him, did just that.

Mohamed Younis 09:00

Now tell us a little bit more about the lawsuit itself. So you mentioned that you lived in an integrated neighborhood. Where -- was the educational system segregated despite the integration of the neighborhoods?

Cheryl Brown Henderson 09:11

The segregation in public education in Kansas was only at the elementary level and only in cities that were 15,000 or larger. So all of the small towns in Kansas that had, you know, a very tiny African American population could not legally operate segregated schools. So a lot of those early cases that I mentioned came from those small towns, and they were illegally segregating. And what they would do -- the one school in the town, maybe the town was, 2, 3, 4,000 people. So they would take one room in the building and make that the "colored classroom"; and by Kansas law, that was illegal. Because African American children, if you were a city that was not first class, you cannot legally segregate.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 10:00

So Topeka, Kansas City and Wichita were the first-class cities where elementary schools were segregated. My mother and my father, my parents, had integrated junior high, integrated high school experiences. And the way they handled the integration at those levels, however -- academics were integrated, but extracurricular activities were segregated. So you had two football teams, two basketball teams, two cheerleading squads, two proms, although you sat in classes together all day in the same building. But anything that was considered social interaction was segregated. My mother was inducted into the National Honor Society in the, in the late 1930s. And that was the one time they had a joint assembly for the entire school. She and another young man were inducted. So I can't explain the theory behind that or the impact of that methodology, but that is the way Kansas chose by law to handle the issues of segregated schools.

Mohamed Younis 11:08

The -- how did the litigation itself sort of impact your family? Do you, did you, did your immediate kind of experience day-to-day, the kids, mom and dad, did your lives change? Obviously changed later when kind of became a monumental case, and here you are, many years later, still telling the story. But in those initial first years, what was it like?

Cheryl Brown Henderson 11:30

Well, for the plaintiffs in Brown v. Board, all of these cases were class actions. And so the Topeka case was filed on behalf of 13 families. We were one of those 13 families. And ironically, we were not alphabetically first. The family of Darlene Brown was alphabetically first. And so we believe the reason our family ended up being the lead family and dad being the lead plaintiff was based on gender. He was the only dad among the parent plaintiffs; the remaining 12 were all women. And as I said, one of them was a woman by the name of Darlene Brown -- no relation, but clearly alphabetically, she would have come first. But Oliver Brown. although not alphabetically first, he was the only man. And he was the 10th person to sign on as a plaintiff. So he was not even the first person to step forward to volunteer to be a plaintiff.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 12:26

So a lot of those myths that are out there -- I call them "urban legends" -- are patently false, and I take great delight in educating people about what, what really happened. so immediately in the aftermath of Brown v Board, no, it didn't impact our family in negative ways. You think about the pushback that we hear about in the South, and you think about the, the violence sometimes that emerged or emanated from people now having to open their doors of their schools to all children. We did not have that experience. And I think because we already lived around one another, you know, racially, and worked in settings, our churches you hear. So it was an easier transition.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 13:09

So in May of 1954, when the Supreme Court announced its opinion in Brown, in September of 1954, the schools in our community integrated. And even the teachers were then integrated into the schools. However, for one year, the school board had a policy for the African American teachers that were now in schools that had been formally segregated White schools, the principals of those schools had to personally call every single parent of White children at that grade level. So let's say I'm an African American fifth-grade teacher for the first time in this school. Well, the principal would call every parent of White fifth graders to see if they would accept having that Black teacher. And he, they discovered that no one said, "No." So it was something that didn't last as a policy.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 14:03

The school board had tried to divide and conquer in the spring of 1953, you know, knowing that Brown was working its way through the federal court system, the superintendent sent a letter to African American teachers who had been teaching three years or less -- teachers, he considered that were nontenured. And basically he said if the plaintiffs in Brown succeed, you will not have a job because I don't believe there'll be enough White parents willing to have you as their child's teacher for us to keep you on. So in May of 1954, they made good on that. So those teachers were let go, and many of them had to relocate -- to Oklahoma or Colorado, to bordering states where they could, could teach. And we did years later, you know, meet some of those teachers that had to relocate.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 14:56

So you know, the African American community was not monolithic, just as, the same today. And not everyone supported the idea of Brown v. Board; not everyone supported the idea of integrated public education in Topeka, because the African American schools were excellent build, excellent schools. They were beautiful buildings. We didn't have the same issues that they had in the South with facilities or transportation. African American teachers in Topeka held more advanced degrees than the White teachers because there was no other outlet for that master's or postmaster's work. So education was top notch. So we weren't talking about issues of quality, right, of the education or, or transportation. It was the principle of the thing; simply segregation per se, and, and maybe why the U.S. Supreme Court selected the Kansas case as the lead case.

Mohamed Younis 15:51

That is so fascinating because that's exactly opposite of what people think of when you say Brown v. Board of Education. I mean, I went to law school. I was -- Thurgood Marshall is one of the people I admire most in American history, and I didn't know any of this. That is absolutely fascinating. So the cases that sort of get grouped into the desegregation kind of final push, if you will -- Brown v. Board in Kansas; Davis v. Board of Prince Edward County in Virginial Briggs v. Elliot in South Carolina; Bolling v. Sharpe in D.C.; and Belton v. Gebhart in Delaware -- states that really are very different than each other. I know that a big part of your work over the past years has sort of been connecting with the other family members from some of these other cases. What has it been like to sort of learn and compare your experiences together?

Cheryl Brown Henderson 16:46

Well we now have an extended family, and we call it the Brown v. Board family. We were bowled over. When we set out to start the Brown Foundation back in 1988, we had a very simple idea. We thought it would be a mom-and-pop operation; we would give scholarships and have a few programs. And then the realization hit that, wait a minute, we don't know this well enough ourselves to do the job that we're setting out to do. So we had to undertake a massive research effort to find out, what really is Brown v. Board of Education? This was not something we talked about at home. My father passed away when I was only 10 years old -- and it was 1961, shortly after the Brown decision and really it hadn't become something -- exactly. So we really didn't talk about it. We really didn't understand it. We didn't know the impact it would have. So it was, it was a learning curve, even for us.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 17:42

So in, in undertaking and engaging in the research, oh my goodness, you cannot imagine how surprised I was to learn about the Davis and the Bolling case and the Belton case and Bulah case and, you know, all of those cases and the Dav--, it was amazing to me. It was like having a brand new set of encyclopedia, if you will. So then the next thing was, oh my goodness, here all these cases that are part of Brown; where are the people? So we started reaching out to people that we knew and connecting the dots and somebody would know someone else. And eventually we were able to connect with all five cases and litigants from all five cases. This is contemporary history. So, many of these people are still living. And in the case of the plaintiffs in Virginia and the people who brought the Virginia case, they were teenagers, you know, 17-, 18-year-olds. So they were young folks, if you will, in a contemporary sense.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 18:38

So we were Not only thrilled but just hearing their story -- their experiences were completely different than the experience of those of us in Kansas. From Delaware to South Carolina to Virginia, everyone had a unique story. For example, South Carolina was all about transportation, you know, having to walk eight miles one way to school. We were reminded that oftentimes In the South, African American young people would be 19 and 20 years old, graduating high school. The reason being they were not physically strong enough at five and six years old, sometimes seven, to walk eight miles to school. So parents would wait, and maybe they would start school when they were nine, you know, and physically able to make that trek to school.

Mohamed Younis 19:25

That's amazing. So that sets them back.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 19:26

Yeah, so there are all these little nuances and all of these barriers that were thrown up, you know, to our achieving and, and really even getting an education.

Mohamed Younis 19:37

Fascinating. I want to ask you, what have been some of the most memorable moments or experiences you've had in sharing the story of your family. I know you've also not only shared it with audiences across the 50 states, but also globally. What, what's kind of something that stands out to you as a memorable part of this journey for you?

Cheryl Brown Henderson 19:56

I think it's the, the sense of awakening that people believe, people know about court decisions, you know. They know Brown v. Board of Education. They have no idea who Brown is. They have no idea that the judicial system uses shorthand et al., et alia, meaning "and others." They certainly were not aware that there were others. And not that, the number, the sheer numbers of the others, you know, several hundred people. And people know Thurgood Marshall; they were not aware of Charles Houston. You know, they weren't aware of Constance Baker Motley, one woman on the legal team. They weren't aware of Jack Greenberg, you know, one White male on the legal team. So it is always, it feels good to watch the kind of the, the -- the eyes will light up and people will think, "Oh my goodness, you know, I didn't, I didn't know that." And they want to know, you know, "Tell me more." And I think it's fascinating that Briggs v. Elliot was the first case to reach the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal. But when Brown v. Board came to the court, it represented a different opportunity, because Kansas was a border state. Kansas had not been a state that experienced slavery. Kansas was simply testing segregation per se because the buildings were sensibly equal. Teacher pay, all of those things that weren't the case in the South, you know, were true in Kansas. So we can't help but think that the court looked at Kansas as an opportunity to really, let's talk about this in terms of just segregation per se and the violation of the Equal Protection Clause.

Mohamed Younis 21:41

As a purely legal issue, not an equitable issue of access to education. That is, that's absolutely a nuance I had no idea -- that that was, that's amazing. OK, I want to ask you about today in America. So, we obviously, at Â鶹´«Ã½AV, we do a lot of public opinion surveys. Today, we released some data that show that 52% of Americans still think that racial segregation is a serious problem in today's schools in America. Give me your reaction to that and sort of where you, improvement can be made.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 22:12

Yeah, I agree with them. My question is always, when someone says to me, "Schools are resegregating," my follow-up question is, "Did they ever desegregate?" So when you look at, in the aftermath of Brown, you know, in that from 1954 probably to '56, you know, a few hundred did desegregate. Because you have to realize, not the entire country was segregated. So we are looking principally at the South and at the Eastern seaboard and, you know, some of the states that, Missouri and, and Texas, but we're not looking at the entire country. So a few hundred schools did desegregate immediately.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 22:51

However, in 1957, although they started this process in '56, just two years after Brown v. Board, the United States Congress entered the pushback, drafting a document called something about constitutional principles, but it's commonly known as the Southern Manifesto. Basically, nearly 100 elected officials in the House and the Senate signed this document. And it was a document of defiance, and basically said the Supreme Court had overstepped its bounds. It was judicial overreach. We're gonna do everything in our power to overturn Brown v. Board. For you, school districts in the South that are planning to defy, you know, don't worry; we have your back. This is coming from Congress. So when you look at it that way, there was no rush to comply. They were being encouraged to drag their feet. When the court reconvened that next year and issued its mandate for how they wanted Brown implemented, and they came up with the infamous phrase, "with all deliberate speed." The word "deliberate" means slow, and it means painstakingly slow.

Mohamed Younis 24:06

Comes from "deliberation."

Cheryl Brown Henderson 24:07

Thank you. So we have to wonder, with all the messages, you know, you have Congress saying, "Don't worry; we're gonna work at overturning this. They overstepped their bounds. It's overreach." You have the Supreme Court itself saying, you know, be deliberate about, you know, your making this change. So there should be no wonder that not many school districts or many schools really did desegregate. So as neighborhoods changed; as we experienced "White flight," which was something the legal team -- a term they were not familiar with. You know, so many things happened in the wake of Brown. The pushback was not only immediate; it was protracted, and it continues to this day.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 24:52

So I am not surprised, and I certainly think that we need to look more at how many actually did comply, and not so much as "Oh my goodness! Schools are resegregating." Now, the troubling part of all of this to me is that while the court is winding down -- there are not so many court cases anymore or court order deseg; people are being granted unitary status, saying, OK, you've tried your best, basically. You have magnet schools, you know, you can be relieved now of your busing programs. And then you have the Milliken case in in Michigan that really absolved the suburbs from being part of any desegregation opportunities, you know, so how does that work? So if you're, if you're ringed by suburbs and have the urban core, you have White flight in the urban core, and it's becoming browner and browner and more impoverished. And now you're saying, OK, the suburbs can't be part of this, where the resources have gone. They fled along with Whites who left the urban -- yeah, exactly. So what do we expect?

Cheryl Brown Henderson 26:00

So I think it's now, we need to be very real about this and rather than, you know gnash our teeth and wring our hands about who's sitting in those classrooms, we need to be more focused on achievement. We need to be more focused on, just because my school is predominated by, by Black or Brown children doesn't mean it shouldn't still be a world-class experience. You know, we allow people off the hook; we go along with that. There is a cottage industry around statistics about how awful, you know, some schools are. There is a cottage industry, and degrees are awarded, dissertations are written, books are written about, oh my goodness, you know. To me, that is unconscionable.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 26:51

You know, if you're gonna spend that kind of time, let's spend that time talking about, let's assess what's going on here. Let's take a look at how we can make it better. How can we support our teachers? Rather than using it as an opportunity to enrich ourselves, rather than -- and, and the children are the ones that lose. They are the ones that we scapegoat. There should be AP classes in every urban school. You know, there should not be schools without, you know, functioning toilets or gymnasiums that have leaky roofs. Children are very smart, and they know when they don't matter. You know, we act as though they are props and not real. You treat children that way, you know, you create angry masses, if you will. Because their frustration at not having the command of the written word or of being able to engage in mathematics or to be able to code a computer -- their frustration is on you. You know, so don't think they don't know why it is that they've come up short.

Mohamed Younis 28:01

On that very powerful note, Cheryl Brown Henderson, thank you for joining us on the podcast.

Cheryl Brown Henderson 28:05

Thank you.

Mohamed Younis 28:07

That's our show. For more learning on the experience of Black Americans, check out the work of the Â鶹´«Ã½AV Center on Black Voices.