Story Highlights

- Most Russians (68%) say inequality has increased since 2011

- Older adults are more likely than young people to agree

- Worsening living standards and perceived widespread corruption play a role

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Protests in Russia last month highlight the growing frustration many Russians have with and the increasingly worse inequality they see in their country. The majority of adults in Russia (68%) surveyed last year say the difference between rich and poor has increased in the past five years. Only four other former Soviet states surveyed have higher percentages of people who say the difference has increased in the past five years -- Armenia (79%), Ukraine (77%), Moldova (77%) and Lithuania (75%).

In addition, while young Russians are protesting in the streets, they are not the only ones who see the disparities. Older Russians are more likely to say that difference "has increased": The vast majority (77%) of people aged 55 and older -- near the retirement age in Russia -- feel that way.

Even among young people between the ages of 15 and 24, whom other Â鶹´«Ã½AV research shows tend to have a more optimistic worldview, the percentage who says the difference "has increased" is still at the majority (55%) level.

Worsening Living Standards, Corruption Are Factors in Gap

The personal financial situation of Russian residents plays a role in their perceptions of the inequality between the rich and the poor over the past five years. The percentage of Russians who say their living standards are getting worse has more than doubled in the past several years: More than one in three (36%) Russians said their standard of living was getting worse in 2016, compared with about one in six (17%) in 2014.

Seventy-nine percent of those who say that their standard of living is getting worse say that inequality has increased, compared with 61% of those who say their standard of living is getting better. But even in this group of people who say their standard of living is getting better, the majority still think the difference between rich and poor has increased.

These perceptions about inequality seem unrelated to the actual wealth of Russians; there is only a four-percentage-point difference in perceptions between those whose incomes are in the poorest 20% of the population and those with incomes in the richest 20%.

Corruption is yet another important factor in their attitudes: 74% of those who say corruption is widespread throughout the government in Russia also say the difference between rich and poor has increased, compared with 45% of those who say no.

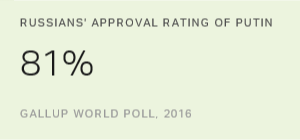

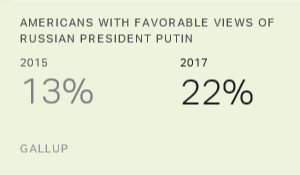

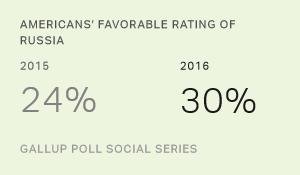

While these differences are striking, it is important to remember that neither Russia's economic downturn nor corruption has affected Russian President Vladimir in recent years.

Life Ratings and Perceptions of Inequality Are Related

Â鶹´«Ã½AV classifies people as thriving if they rate their current lives a 7 or higher and their lives in five years an 8 or higher on a ladder scale (based on the ) with steps numbered from zero to 10, where zero represents the worst possible life and 10 represents the best possible life. People are considered suffering if they rate their current and future lives a 4 or lower. Those in the middle fall into the struggling category.

In 2016, 13% of Russian adults rated their lives poorly enough to be considered suffering, 58% were struggling and 29% rated their lives positively enough to be considered thriving.

Russian adults who are suffering are more likely -- by a wide margin -- than people who are thriving to say the difference between rich and poor people in Russia has increased in the last five years (81% vs. 59%). Russians who are struggling fall in the middle with 68%.

Implications

These findings show that based on Russians' sentiment, the perception that the protests in Russia are a youth phenomenon is not entirely accurate. Although the majority of young people see increased inequality between rich and poor in Russia, the percentage of people aged 55 or older who say inequality has increased is even higher.

While people tend to become less optimistic with age, Russian adults facing retirement may also be more aware of how the last two years of recession could affect them personally. In August 2016, the Russian Reserve Fund had fallen to $32.2 billion, compared with $142.6 billion in 2008 when it was at its highest. The drop may lead to the Kremlin taking funds from the Welfare Fund, which is intended to fund future pensions and investment projects.

Also in August 2016, the Russian government announced that pensions would not be raised to match inflation like in previous years. As it stands, Russian pensions average $187 a month.

In light of these economic problems, it seems that the perception among Russians of growing inequality is grounded in reality. As the Russian public becomes more aware of the problems, it still remains unlikely that they will affect Putin's approval rating.

With no change of leadership in sight, it is also unlikely that the perception of rising inequality in Russia will change in the near future.

Julie Ray contributed to this story.

Survey Methods

Results are based on face-to-face interviews with 2,000 adults in Russia, aged 15 and older, conducted from April to June 2016. For results based on the total sample of national adults, the margin of sampling error is ±2.7 percentage points. The margin of error reflects the influence of data weighting. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

The Chechen Republic, Republic of Ingushetia, Republic of Dagestan and the Republic of Crimea were excluded due to political instability. The Republic of Adygeya, Republic of Kabardino-Balkaria, Republic of Karachaevo-Cherkessie and North Ossetia were excluded due to high crime levels. Remote small settlements in far-Eastern Siberia were also excluded. The excluded areas represent about 6% of the population.

Learn more about how the works.