Story Highlights

- Majorities see widespread government corruption

- Barely more than one-third are confident in national government

- Few are confident in honesty of elections

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- 2018 is an important political year in Latin America, as residents in four of the region's most populous countries -- Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela -- vote for president. On May 20, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro won a new term in an election international observers have described as a "sham." On Sunday, Colombians elected right-wing Sen. Ivan Duque over his left-wing challenger Gustavo Petro. Next up is Mexico's presidential election on July 1, followed by Brazil's on Oct. 7.

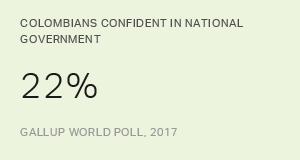

Maduro's victory notwithstanding, public opinion trends suggest residents in many of the region's countries are eager to break with the status quo. Across 21 Latin American countries in 2017, a median of 35% of residents said they have confidence in their national government; that figure represents an upswing from 29% in 2016 (though it remains lower than the mid-40s range recorded from 2009 to 2011). However, in none of the four largest countries with presidential elections this year were more than 26% of residents confident in their national government; this figure was lowest in Brazil at 17%.

Frustration with high-level corruption and economic stagnation largely explain Latin Americans' growing discontent. The popularity of the region's left-wing leaders in the 2000s was based largely on largesse from the commodities boom they enjoyed at the time. Latin American economies grew around 6% on average between 2003 and 2008, moving 70 to 80 million low-income residents to the middle class. For many, heightened expectations from that period have turned to disappointment and discontent as commodity prices fell after 2010, sharply curtailing growth in most countries.

Since 2015, Latin Americans have been at least as likely to say their local economies are getting worse as they are to say they are getting better -- a contrast from the optimism that prevailed between 2010 and 2013. Though economic activity is slowly picking up in the region, its long-term growth prospects remain weak.

Corruption scandals have further undermined confidence in many Latin American leaders; corruption is a major issue in all four of the larger countries holding presidential elections this year. Maduro's regime has driven Venezuela to a full-blown humanitarian crisis, and international observers say his re-election amid catastrophic economic conditions and record-low voter turnout says more about his ability to manipulate the electoral process than about his popular support. In Brazil, the current president and four former presidents -- including the enormously popular Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva -- are in prison or under investigation.

Region-wide, three-fourths of Latin Americans (75%) currently say corruption is widespread in their country's government. In Mexico, this sentiment soared from 63% in 2014 to 83% in 2016 as President Enrique Peña Nieto became embroiled in numerous scandals, including one involving his ties to contractors awarded lucrative government deals. In 2017, it remained high at 80%.

Beyond making it difficult to trust any specific leader or party, endemic corruption has not helped the lack of faith in democratic institutions across much of Latin America. Particularly troublesome in a year of pivotal presidential contests, a median one-third of residents across the region (34%) say they have confidence in the honesty of elections in their country, a figure that has changed little over the past decade. Currently fewer than one in five residents have faith in their country's elections in Mexico (18%), Colombia (16%) and Brazil (14%).

This lack of confidence may have serious consequences. Citizens who feel the entire system is rigged to benefit powerful elites may view any form of political participation -- including voting -- as futile. If the result is low turnout in this year's elections, it will become more likely that more extreme candidates -- those who are able to mobilize smaller groups of ardent supporters -- will be successful, possibly contributing to the political instability and mistrust afflicting the region.

Implications

Growing public discontent with government in much of Latin America suggests the potential for instability in the region has increased in recent years. Systemic problems like corruption may lead many to conclude that only by subverting existing institutions -- through insurgency or revolution, for example -- can they hope for real improvement.

That makes this year's elections all the more important. Many of the region's residents -- particularly its millions of social media-savvy young people -- are counting on the election results to produce meaningful change. In Brazil, for example, millennial activists are forming new political "startups" -- civic movements that are shaking up the established political order.

If the anti-corruption fervor now present in much of the region helps elect candidates with a credible claim to tackling the problem, public perceptions will likely improve and the threat of instability may subside. If, on the other hand, Latin Americans end up feeling that this year's elections simply reinforced the status quo -- as was the case in Venezuela -- discontent may continue to mount.

Survey Methods

Results are based on face-to-face interviews with approximately 1,000 adults, aged 15 and older, conducted each year in 21 Latin American countries. For results based on the total sample of national adults, the margin of sampling error ranged from ±3.5 percentage points to ±5.4 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. All reported margins of sampling error include computed design effects for weighting.