A Conversation with Dr. Gwendolyn Sasse

Director of the Centre for Eastern European and International Studies

It has been five years since the Euromaidan revolution, and Ukrainians are still waiting for many of the reforms they were promised. What do you see as the top priority for Ukraine's next president -- whomever that will be -- and its next government?

Sasse: Socio-economic issues, corruption and the ongoing war in the Donbass have been the three top concerns of the Ukrainian population for a while. Identity issues related to the war and corruption have figured prominently in the election campaign. In turn, they have crowded out a more detailed debate on social and economic policies.

The incumbent President Petro Poroshenko has built his campaign around his role as the defender of the Ukrainian nation against Russian aggression, while his opponents Yuliya Tymoshenko and Volodymyr Zelensky have tried to capitalize on the fact that the anti-corruption reforms have stalled under Poroshenko.

Tymoshenko has been the only candidate with a chance of winning who has tried to address socio-economic issues, mostly in the form of unrealistic promises, such as lowering utility tariffs. However, over time she has toned down this part of her campaign, focusing instead on Poroshenko's failure to stop corruption and on his own alleged involvement in corruption.

The next president of Ukraine, whoever he/she is, will have to quickly demonstrate that they have a coherent plan for proceeding with reforms, especially anti-corruption reforms, to deliver both socio-economic returns to households and small- and medium-size enterprises and a sense of regime legitimacy. The biggest challenge will be to restore the public's trust in national-level politicians and institutions that has reached an all-time low since the Euromaidan.

What has changed in Ukraine since Euromaidan? Either for the better or for the worse?

Sasse: Under Poroshenko, Ukraine has embarked on the most comprehensive reform process since 1991. Among the reform successes are the ongoing decentralization process, economic reforms limiting the scope for oligarchs in some sectors, the establishment of anti-corruption institutions and, more generally speaking, a critical influence of civil society actors and young parliamentarians shaping reform legislation and monitoring implementation.

Most of the reforms remain incomplete, however, and in particular with regard to anti-corruption, the newly created monitoring and judicial bodies remain incomplete and lack the capacity to follow through from compiling the evidence to bringing cases to court and actually sentencing individuals.

Somewhat paradoxically, the general population is as disenchanted with national-level politics now as before the Euromaidan. This is not to be confused with a wish to return to the pre-Euromaidan times; it is best understood as a direct consequence of the mass mobilization around the time of the Euromaidan and the high expectations this process generated.

It has also been five years since Crimea joined Russia, and the conflict in the Donbass is still ongoing. What role will relations with Russia play as Ukraine works to end the fighting and recover from the conflict?

Sasse: So far there is little sign of either Russia or Ukraine actively trying to end the war. Russia's role is critical in this regard, but it is fair to say that the Ukrainian government's attempts at reintegration or even addressing local needs in the Donbass have been limited in recent years and that Poroshenko has utilized the war in his electoral campaign. Here the question is if a new president could reprioritize the needs of the local population.

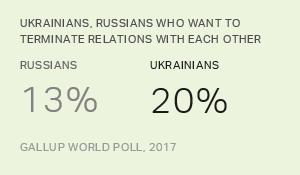

There is speculation whether Zelensky or Tymoshenko would attempt to make a "deal" with Russia, either on the Donbass or on economic issues. While Poroshenko's departure might open up some space for dialogue with Moscow, it is highly unlikely that Russian-Ukrainian relations will improve in the foreseeable future under Russian President Vladimir Putin.

It suits current Russian interests to retain a degree of leverage over Ukrainian politics through the Donbass issue and the gas transit to Western Europe bypassing Ukraine when Nord Stream 2 is completed. There is some indication in Russian opinion polls that the costs of the Donbass war are getting harder to justify. This might induce a greater willingness to negotiate, for example, to enable a UN peace mission. The issue of Crimea is considered settled by Russia and Russian public opinion. Here the only imaginable change would have to come from the Crimean population itself in the post-Putin era.

As a follow-up to that, what about the West?

Sasse: The experience of the Euromaidan and the war have put Ukraine on a decidedly pro-Western course. The IMF, the U.S., the EU and individual EU member states have stepped up their financial and political support of Ukraine's reform process significantly since the Euromaidan. The EU's Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement and visa-free travel to the EU are in place, and the U.S. and the EU have implemented a sanctions regime against Russia in reaction to the annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine and might extend sanctions in reaction to the military escalation in the Azov Sea.

Support for EU and NATO membership has increased in Ukraine, although it varies across regions. Poroshenko has made membership in both institutions an explicit goal anchored in the constitution, but neither the EU nor NATO are likely to offer Ukraine an explicit membership perspective beyond the current forms of cooperation. This hesitation is reinforced by the strained transatlantic relationship and internal challenges of the EU.

Sasse has been the Director of the Centre for Eastern Europe and International Studies since 2016. She is Professor of Comparative Politics at the Department of Politics and International Relations and at the School of Interdisciplinary Area Studies at the University of Oxford, and is Professorial Fellow at Nuffield College and a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at Carnegie Europe.

The views of those interviewed are expressly their own.