GALLUP NEWS SERVICE

"There are many ways to overcome danger if a person is at least willing to say or do something." -- Socrates

PRINCETON, NJ -- Russian President Vladimir Putin has, at times, faced considerable public anger about security conditions in his country. Following the Beslan school tragedy of 2004, during which 344 civilians died in a hostage standoff between Chechen separatists and Russian security forces, tens of thousands of people gathered at the Kremlin to protest the government's perceived failure to fight terrorism. Putin recognized that failure, but immediately noted that similar shortcomings can be seen even in flourishing countries such as the United States, Spain, and Great Britain. Little wonder, he noted, that it is a challenge for Russia, which was impaired by the disintegration of the USSR.

Putin's point about terrorism is certainly valid, but Â鶹´«Ã½AV World Poll data suggest that Russians' insecurity regarding their personal safety runs particularly deep -- with many saying they feel unsafe in their day-to-day lives. When asked, "Do you feel safe walking alone at night in the city/settlement/village where you live?", only 27% of Russians answer affirmatively. In most developed nations, the corresponding figure is somewhere between 60% and 80%; but even in other former Communist bloc countries like Belarus and Kyrgyzstan, it tends to be somewhat higher than in Russia. Only in Ukraine is it statistically similar, at 30%.

The question, "In the area where you live, do you have confidence in the local police force or not?" produced a similarly uneasy result; just one-quarter of Russians (25%) responded affirmatively.* Again, comparative figures from developed countries are far higher (United States: 80%, France: 71%, United Kingdom: 69%, Japan: 69%), and even those from other former Soviet republics tend to be somewhat higher (Belarus: 46%, Latvia: 45%, Kyrgyzstan: 30%, Lithuania, 40%). Again, Ukrainians (24%) are about as likely as Russians to express confidence.

Russians were also asked whether they personally have fallen victim to two common types of crime -- theft and assault -- in the past year. To the question, "Within the past 12 months have you had money or property stolen from you or another family member?", 17% say yes -- a fairly high proportion by global standards (in India, for example, the corresponding figure is 6%, in Japan it is 5%), though comparable to those in the United States (16%) and the United Kingdom (15%), as well as those in most other former Soviet republics. To the question "Have you been personally assaulted or mugged within the last 12 months?" just 5% of Russians give an affirmative response. Results were similar in developed countries (United States: 3%, United Kingdom: 6%, France: 6%) as well as in other former Soviet republics (Estonia 5%, Belarus: 3%, Ukraine: 4%).

Why Don't Russians Feel More Secure?

If Russians are not significantly more likely than those in other countries to say they have been recent crime victims, why do they seem particularly sensitive about their personal security? One possible answer is that corruption is so endemic to Russian society that even if they are not technically victims of theft or assault, most Russians constantly struggle to avoid being taken advantage of by crooked officials. Widespread corruption among Russian police forces, for example, is undoubtedly part of the reason just 25% of Russians express confidence in the police.**

Another possible factor is the idea that many Russians remember feeling more secure prior to the collapse of the USSR. More than three out of four Russians (78%) say they think crime is higher than it was in the Soviet Union days, while 13% feel it has remained the same, and only 2% answer lower.

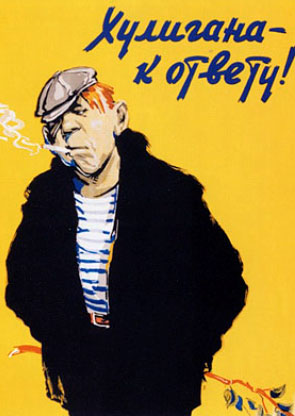

The perceived difference may be heightened by changes in the news media that Russians are exposed to. The Soviet Union never allowed its news media to expound daily on the defects of society, as Russian news media increasingly do -- or to sensationalize acts of violence. On the contrary, Soviet propaganda possessed a prim and proper quality, and was by modern standards, rather naive. Below is a sample of the Soviet propaganda -- a poster from 1958 exclaiming "The Hoodlum Must Pay!"***

Racial Violence on the Rise

One threat to personal security that is omnipresent in the Russian news media comes from fascist youth factions that perpetuate hate crimes against ethnic minority groups. Their targets have been not only Africans and Asians, or migrants from former southern Soviet republics from Transcaucasia and Central Asia. Victims have also been Russian citizens who live in the republics of Russia's North Caucasus area and possess physical features distinguishing them as being of minority descent.

The results are evident: in answering the question, "Have you heard about the activities of 'skinheads'?", 71% of respondents answer affirmatively. Among that group, just 3% say they approve of the skinheads' activities. Somewhat disturbingly however, that number rises to 11% among Russians aged 15 to 24.

Thus, a paradoxical situation is taking shape regarding racially motivated crimes: Russian politicians frequently protest attempts by the Baltic countries to rehabilitate their own veterans who participated in the Nazi atrocities of World War II. However, despite the Kremlin's frequent attempts to rein in the violence by launching different youth projects, they have become increasingly unable to control the nationalistic and racial aggression of Russia's own young people.

*Â In Russia, there is no "local" police force in the strict sense of the word -- all law enforcement forces are under federal jurisdiction.

**Ìý³§±ð±ð Corruption in Russia: Greasing the Wheels to Get By

***Ìý³ó³Ù³Ù±è://±è´Ç²õ³Ù±ð°ù²õ.°ì°ù²¹±¹.°ù³Ü/¾±»å/2343.³ó³Ù³¾±ô

Survey Methods

Results are based on face-to-face interviews conducted in February 2006 with a randomly selected national sample of 2,011 Russian adults, aged 15 and older. For results based on these samples, one can say with 95% confidence that the maximum error attributable to sampling and other random effects is ±2.4 percentage points. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.