The future of the global workforce -- and by extension, future prosperity and well-being worldwide -- relies in no small part on establishing better links between jobs and education. That theme resounded strongly throughout the day at Diplomatic Courier magazine's annual Global Talent Summit, hosted by Â鶹´«Ã½AV in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 13.

On some level, the need for education to better equip students to find good jobs is so obvious that it seems strange the topic is even worthy of discussion. But that dialogue is as important today as it's ever been. The lackluster, uneven recovery from the global recession in the developed world; the commodities bust that has slammed recent rapid growth in many emerging markets to a halt; and increasingly toxic levels of youth unemployment in many countries -- all of these speak to a desperate need for new ways to release currently untapped human capital around the world.

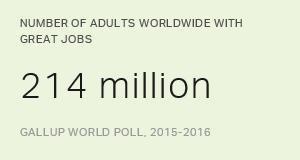

Â鶹´«Ã½AV CEO Jim Clifton framed the discussion in the event's keynote address by arguing that the stakes are higher than they were for previous generations because for many young people, the notion of a good job now represents far more than financial security and the ability to support a family. Millennials, in particular, are searching for jobs that also serve as a source of fulfillment and self-expression: "If your job doesn't have meaning, your life doesn't have meaning," Clifton said. "So if employers are not dealing with purpose, they're not dealing with the whole individual."

Other participants described how their organizations are working to match education and training with labor market needs through a range of innovative strategies. In some cases, this means providing opportunities for more highly targeted training that does not place as heavy of a burden on those for whom traditional higher education may be out of reach. Robert Nicholson of the national nonprofit NPower spoke about how his organization bridges the technology skills gap between 1) underserved veterans and young people and 2) tech companies seeking new sources of talent and energy.

Aligning jobs and education also means adapting traditional educational curricula to better address the need for business growth as a fundamental engine of job creation. Clifton called for an increased focus in schools on identifying and nurturing entrepreneurial talent so that young people are better prepared to build enterprises that accelerate economic growth: "We have to make the development of entrepreneurs more intentional because innovation has no value without a customer standing next to it."

From a global perspective, overcoming the education-employment gap may even mean exporting knowledge and experience from businesses in the developed world to lower educational barriers to economic participation in the developing world. Andrew Mack of AMGlobal Consulting shifted the focus to employment in the developing world in describing the role of microfranchises -- i.e., small-scale franchises that give low-income people the opportunity to run businesses without having to overcome the far more daunting barriers associated with starting a business from scratch.

Whatever the approach, any strategy for bridging the gap between schools and employers requires active participation on both sides. Universities are among the most important venues for such partnerships. As Larry Quinlan, Chief Information Officer at Deloitte, noted, "A lot of experiential learning can't be provided by schools. There's a huge argument for corporate investment in education far beyond money."

However, as Quinlan also said, maintaining crucial links between education and the workplace is often a far more arduous task than one might expect. Lowering the barriers between the two worlds requires creativity, resolve and a dose of humility. But as many of the summit's participants demonstrated, there may be no more important effort toward helping young people around the world attain good jobs and good lives.