For the roughly 5 million people living in Iraqi Kurdistan, a semi-autonomous region in Iraq’s north, the 2003 U.S.-led invasion played out considerably differently than it did in Iraq’s south. Instead of economic ruin, the invasion ushered in an economic boom, and instead of instability, it brought feuding Kurdish political parties together.

And unlike in the south, the invasion generated goodwill for the U.S. that is still present today. In late 2022, nearly four in five adults in Iraq’s Kurdish region (79%) said they approved of U.S. leadership, making Iraqi Kurdistan the most pro-American political entity in the Middle East at any time, even more so than historical U.S. ally, Israel (67% in 2017 and 2018). In contrast, across the rest of Iraq, 28% of residents approved of U.S. leadership.

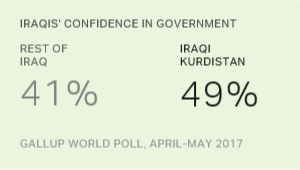

While a review of Â鶹´«Ã½AV data over the past two decades shows that Iraqi Kurdistan, in many respects, has been Iraq’s success story, the latest surveys in the country suggest economic unease may be putting these gains at risk.

Spared the Horrors of War, Most Feel Safe in the Kurdish North

Since the Gulf War, U.S. actions in northern Iraq have limited both internal and external sources of instability, promoting Iraqi Kurdistan’s autonomy and helping to lay the groundwork for the relative safety and prosperity it enjoys today.

From 2003, Kurdish security forces were largely able to control their borders with the rest of Iraq and deal effectively with terrorist threats. Spared from the conflict afflicting the rest of Iraq, in 2008, 56% of residents within Iraq’s Kurdish region reported feeling safe walking alone at night in their city or area, 13 percentage points higher than in the rest of the country.

By 2022, nearly nine in 10 adults in Iraqi Kurdistan (88%) reported feeling safe walking alone at night, a sentiment similar to that in low-crime Gulf states, and much higher than the 72% in the rest of Iraq.

Iraqi Kurdistan, a Sanctuary for Iraq’s Embattled Minorities

As much of the rest of Iraq either resisted U.S. occupation or collapsed entirely into sectarian civil conflict, the relative peace and stability of Iraqi Kurdistan drew internally displaced people and vulnerable minorities from other parts of the country -- in particular, Iraq’s ancient Christian communities, which are mostly ethnic Assyrians. Once estimated at 1.5 million before the war, as few as 200,000 Iraqi Christians remain in the country today, with roughly half thought to now be living in the Kurdish region.

Reflective of the sanctuary that the region has become for the country’s minority groups, 84% in areas administered by the Kurdistan Regional Government say their city or area is a good place for ethnic or racial minorities.

This figure is significantly higher than in the rest of Iraq (59%) and higher than anywhere else Â鶹´«Ã½AV has asked this question in the Middle East, by a significant margin.

No Longer Economically Exceptional to Rest of Iraq

Safe, welcoming and pro-Western in outlook, Iraqi Kurdistan has been a more attractive investment environment compared with the rest of Iraq. But while skyscrapers and ambitious real estate projects have shot up in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah, the economic perspective of average residents in the region now mirrors that of other Iraqis.

In 2022, two in three residents in Iraqi Kurdistan (66%) said it’s a bad time to find a job, similar to the 65% who said the same in the rest of Iraq. Further, those living in Kurdish areas are now less satisfied than other Iraqis with what they can buy and do (45% vs. 72%, respectively).

As wellbeing improved in Iraq proper after it emerged from decades of conflict, the Kurdish north appears a victim of high expectations as residents see their own economic opportunities wane.

In 2008, far fewer living in the region (9%) rated their lives poorly enough to be considered “suffering” than their counterparts in the rest of Iraq (34%). In 2022, nearly twice as many in the region were suffering (16%), similar to the level in the rest of Iraq (18%).

Bottom Line

Twenty years after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, the country’s Kurdish north has experienced an entirely different kind of war. Suicide bombings, sectarian bloodshed and volatile politics all too common in Baghdad throughout the country’s darkest periods have known little place in the largely autonomous region.

Strong U.S. partnership and intra-Kurdish unity, while at times tenuous, have ensured the region remains a relative bastion of security. Nonetheless, its political and economic gains continue to be tested.

Shia militias, resurgent Islamic State (IS) group cells and Iran have all struck at Kurdish forces or territory since the 2017 defeat of the IS at the battle of Mosul. Meanwhile, economic discontent continues to simmer, driven by unreliable public services, unemployment and perceived corruption.

Â鶹´«Ã½AV data over the past 15 years tell a tale of two wars -- one in which basic safety and wellbeing suffered greatly after 2003 and one in which peace gave residents a better shot at life. Recent data show that the country could be coming to the end of that chapter as Iraqis’ experiences with economic and personal wellbeing begin to look more similar.

To stay up to date with the latest Â鶹´«Ã½AV News insights and updates, .

For complete methodology and specific survey dates, please review .

Learn more about how the works.